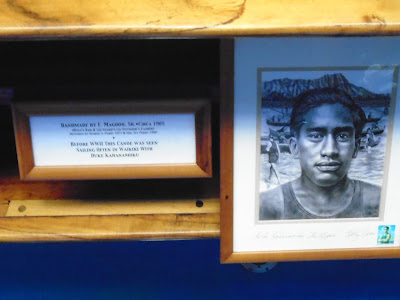

When we were at the pro surfing competition on the Gold Coast, certain surfers were identified as being from Hawaii, as distinct from the U.S.A. I thought this was odd, since—birther liars notwithstanding—Hawaii has been a state since 1959. But having now been there, I can see why the birthplace of surfing has its own identity. Hawaii is proud that its greatest Olympic athlete, Duke Kahanamoku, actually introduced the sport of surfing to Australia.

|

| Portrait of Duke at Hula's Bar and Lei Stand, Waikiki Beach, where we celebrated Pride |

We arrived in Hawaii on an endless Friday. I say “endless” because we left Sydney on Friday afternoon, but then crossed the International Date Line, landing in Honolulu on the same Friday morning. Traveling east over all these months, we “lost” the day so gradually that we hadn’t noticed. We sure noticed when we got it back though!

In a recent post, I addressed the concerns of some travelers to the U.S. (including citizens) who are hesitant even to cross the Canadian border, lest they be interrogated on the way back. It is ironic that on this entry to the States, I was actually greeted with “Welcome home.” It’s touching even though I haven’t lived here for eighteen years. I fully expected more questioning on this trip simply because T. is a non-citizen and we were coming in on a one-way ticket. In these circumstances, it is normal to be asked about one’s travel plans, proof of when one will leave, not to mention how have we been managing to travel in all these countries for over a year?

But no questions of the kind were asked. Instead, the immigration officer said “Welcome to you as well.” They went through their fingerprinting rigamarole and then he asked if I had a Canadian passport too. It turned out that when we checked in for our flight from Australia, I had presented my U.S. passport (the correct thing to do) but the airline official had asked if I had another one, because she was looking for my Australian visa. The only people who needed to see that were immigration when I left the country, but I showed her my Canadian passport anyway, and evidently she’d swiped it into the Advance Passenger Information—which is how the Americans could see it. In any case, showing my U.S. passport was the correct thing to do in the U.S.

Then he asked about our customs declaration (we had recently been on a farm). “You’ll have to talk to agriculture about that,” he said, and waved us through. We couldn’t find agriculture and were on our way out with our bags when another officer, full of Aloha, saw our cards and said “Do me a favor and speak to agriculture about that.”

“Where are they?”

“Speak to someone without a gun,” he clarified.

Well, who doesn’t have a gun in America? Agriculture officers, I guess. They didn’t ask about the farm at all, just what food we were bringing. I’d heard that Honolulu was a more laid-back port of entry than, say, Los Angeles, but this was as relaxed a time as I’ve ever had—and I was born here.

The Honolulu airport is maintained by the city government and so it has a kind of throwback feel. Lots of open air, not many concessions, a ’70s concrete kind of vibe. This relaxed tone was a taste of what was to come in Hawaii. It’s one of the United States, but it’s not like other states.

At our Airbnb I switched on the TV for a change. All in the Family. It was an episode that, incredibly, I knew of, in which Michael and Gloria get married. If you remember this show you know that it was groundbreaking at the time. Indeed, I wish that Archie Bunker’s bigotry sounded more out of date than it does. In any case, this is one of those shows, like I Love Lucy, that illustrates how the U.S.A. could do good TV. Not to sound like the Lonely Planet guide, but laughing at ourselves is surely Americans’ saving grace.

We were in the middle of the Pacific Ocean and it still felt kind of like Asia. Let’s be honest—parts of Australia felt a lot like Asia too. The stores were full of Hawaiian drinks (guava, etc.) We had supper at a food court our hosts recommended: very local, no chains, mostly Asian foods. Then we crashed.

Not literally, though there was that rare moment when, according to T., I say calmly from the passenger seat: “You’re on the wrong side of the road.” Renting a car had turned out to be such the opposite of our usual airport experience that we were just glad to get out of there—in a convertible, though not at the price it should have been. It was a little wasted on the island of Oahu, though. We never saw a speed limit over 55 miles per hour, and most of the time we were driving more slowly than that.

Neither of us had ever been to Hawaii before, so we decided to stick to Oahu and explore as much as we could. I don’t know about the rest of the islands, but it felt very military to us. We were staying with an army family, around the corner from an army hospital, and there were bases everywhere. And offers for those in military uniform. At Pearl Harbor we learned that Hawaii was under martial law during the Second World War. It’s obviously different now, but I still got that impression that a lot of the Pacific forces came to be based there and just stayed.

Pearl Harbor was a place we had to go, as first-time visitors to Hawaii. The U.S. entered World War II late, at the end of 1941, and the reason was the Japanese bombing attack on the fleet and aircraft at Pearl Harbor. Overnight, the country went from isolationism (let’s stay out of Europe’s wars) to an unprecedented war effort on both the Pacific and European fronts. The museums at Pearl Harbor, which are free, do a good job of showing why all this happened: Japan’s imperial ambitions in Asia, how they threatened colonies such as Britain’s and France’s (Indochina, anyone?), and what they thought such an audacious attack on the U.S. Navy could achieve.

The museums also show that the war did not start off going well for the U.S., any more than for its allies in Europe. What the generation who grew up in the Great Depression, and the Blitz in Britain, accomplished was truly remarkable, and something I feel more thankful for as there are fewer of them left. Tom Brokaw or whoever coined the phrase “the greatest generation” was not wrong.

Of course, this is personal for me. The members of my family who fought in World War II were in the Pacific theatre. Both my grandfathers were on Oahu during the war, possibly even during the same period. One of them came there some time after being seriously injured; with all the fighting going on, he wasn’t able to get treatment where he was. My great-uncle Clyde was also in the navy, and in fact was already serving when Pearl Harbor was attacked. He was there on December 7, 1941, and badly wounded in the bombing of the U.S.S. Arizona.

It’s free to visit the Arizona memorial. Demand, though, is such that you have to book tickets in advance, or get there early. I got up early the morning before and snagged us a spot. We also were unfortunately unable to dock at the memorial because it is in need of repair, and currently deemed unsafe. But, the navy boat took us around the memorial and we got commentary from a man who was eleven years old at the time, and saw the whole thing happen. He was clearly too young to fight in the Second World War, but he went on to do so in Korea.

Every branch of my family sent men to serve in World War II. When you think that most of the men—more than a thousand—who died on the Arizona were around nineteen years old, it is very sobering. I am not a military buff per se but as in Vietnam, I wanted to understand this story of the war. So we bought tickets and clambered aboard the U.S.S. Bowfin, “the Pearl Harbor avenger,” a submarine that was launched December 7, 1942.

We also toured the U.S.S. Missouri, the last battleship. Many battleships were destroyed in the Pearl Harbor attack, and the subsequent war was fought with aircraft carriers, but the Missouri outlasted the battleship age. She was hit by a kamikaze attack during World War II, and if you tour the ship, you will learn that the captain required the kamikaze pilot to be buried at sea, with his flag, rather than tossed overboard like garbage. “A dead enemy is no longer your enemy,” he told his men, but a brave warrior who fought for his country. Since then, Japanese as well as Americans have honored this act of humanity in the midst of such a vicious war. There is even an exhibition aboard the Missouri about the Japanese pilots and what they—young men themselves—hoped to accomplish with their suicide missions.

That gave me pause. Japan knew by that point that it could not win the war with the U.S., so its only hope lay in making the war too costly; and it did this by showing the Japanese people’s willingness to sacrifice themselves in endless numbers. An invasion of the Japanese home islands would be an unthinkable bloodbath. We all know how the U.S. resolved that issue.

In his masterwork on America in Vietnam, A Bright Shining Lie, Neil Sheehan comments on how much hatred of the “dirty Jap” informed American behavior, not only during World War II but subsequently in the wars in East Asia. The Nazis, after all, had been in power for years, but it took Japan attacking Pearl Harbor to make Americans want to fight. Understandable, but there are less savory reasons too. Germany, not Japan, was an actual threat to the existence of the United States and of free countries. This is literally true. The reason the U.S. developed the atomic bombs that were ultimately dropped on Japan was because of Nazi Germany. Immigrants from Germany told the U.S. government that it had to make nuclear weapons, because Germany was making them. It is thanks to those immigrants that the U.S. got there first. What Japan did to the Allies in the Pacific war was hideous, but can you imagine the world if Adolf Hitler had gotten the atomic bomb?

The U.S.S. Missouri went on to see service in two more wars. She was in Korea, a war that is not talked about as much but which quietly ended the other day—more than sixty years after the ceasefire. Then in the 1980s buildup of American forces, the battleship was revived again. The Missouri fired the first Tomahawk missiles of the Persian Gulf war.

That was the war of my student days. I remember people holding vigils against it. Not the least upset was a young woman in my dorm who had family in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. War looks different when the bombs are falling on you, which I suppose is the lesson of Pearl Harbor. Not for one moment do I think the Persian Gulf conflict was as neat as the videogame version on the War Channel made it appear. But aboard the Missouri, looking at the Pepsi machine and the computer room of 1991 vintage, I thought of the Americans my age who were actually there. And I thought of the Korean war, and of my great-uncle Johnnie, who served there and brought my mom back a little kimono.

Perhaps the finest hour of the Missouri was the day the Japanese surrendered on her deck. She was in Tokyo Bay and Japan’s representatives apparently expected to be killed when they boarded the ship; perhaps that’s what they’d have done to a surrendering enemy. In any case, Douglas MacArthur and some Allied representatives signed some paperwork and it was all over. Imagine the relief of an actual end, a treaty between countries. World War II was the last war the U.S. declared, and V-J Day was the last real victory.

Among them the Arizona, Bowfin, and Missouri represent the beginning, middle, and end of America’s war in the Pacific. Today the Missouri’s big guns are at a 45-degree angle, as they would be to fire a salute. They are in fact saluting the Arizona memorial, beneath which many brothers in arms still lie entombed in their ship.

Of all the brave warriors in the U.S. forces, it was said (by cartoonist Bill Mauldin, among others) that the Nisei were second to none. Nisei were people born in the U.S. (or Canada) whose parents were immigrants from Japan. Some of those parents were interned in camps in the United States, but that didn’t stop their sons from being drafted, or from fighting courageously. The same could be said of the many black troops who were treated far from equally at home, and who were segregated in the armed forces themselves. It’s a great stain on an otherwise honorable time. Somehow America’s largest single ethnic group, German-Americans, did not end up in internment camps.

At Pearl Harbor we met the daughter-in-law of a native Hawaiian, “Uncle Herb,” who was a veteran of that day. Uncle Herb recently passed away, but before that he spent decades volunteering at the memorial and talking to people about his experience. Now his daughter-in-law is carrying on his memory. It reminded me of the stunning tour we had at Auschwitz, where our Polish guide revealed that she was the daughter-in-law of a survivor.

At Pearl Harbor we met the daughter-in-law of a native Hawaiian, “Uncle Herb,” who was a veteran of that day. Uncle Herb recently passed away, but before that he spent decades volunteering at the memorial and talking to people about his experience. Now his daughter-in-law is carrying on his memory. It reminded me of the stunning tour we had at Auschwitz, where our Polish guide revealed that she was the daughter-in-law of a survivor.

It also reminded me of the uncles in my family. After the war and his injuries at Pearl Harbor, Uncle Clyde was stationed in occupied Japan. There he married Aunt KoKo, one of the most delightful Americans I ever met. That is part of the story too.