I never thought you’d hear me say this, but I can’t think of a nicer way to arrive in a big city than Route 66 westbound into Tulsa, Oklahoma.

We weren’t actually sure when we crossed into Oklahoma. All we saw was a sign welcoming us to the Quapaw Nation. As mentioned earlier, there are a number of indigenous nations whose headquarters are now in Oklahoma, and of course these people were in America long before there were state lines. So T. and I weren’t certain when we should turn to one another and say, “We’re not in Kansas anymore!”

I feel like I write this wherever we go in the world, but most people, most of the time, are friendly and try to help us. I keep beating this drum because I can tell the expectation from some of my friends is the opposite. “Is there anything in Kansas or Oklahoma?” or “Why would you go there?” Some would say the same about a major city like Chicago, but I love it. We had a bit of a struggle getting transit cards when we first arrived there (it’s always touch and go with a foreign credit card in the U.S.), but a woman who worked on the El tried hard to help us work the machine, and then ended up letting us ride for free downtown, where we could get things sorted out at a station. When we saw her the next day, she asked where we’d been and what we’d seen, and dusted off a tourists’ transit map she’d been waiting to give someone since 2019. “You [visitors] are like gold,” she said.

Anyway, around Commerce, Oklahoma, we eventually realized we were in our fourth state.

Allen's Fillin' Station, Commerce

The original 1926 alignment of Route 66 across Oklahoma was more than 400 miles. There are still 383 miles of what Jerry McClanahan calls “first generation paving”: sometimes crossing the interstate back and forth to stay on the frontage road, other times upgraded four-lane. In general, as I may have mentioned, when there’s a four-lane or a two-lane, we choose the two-lane. When there’s a dirt or gravel option, we choose that.

|

| Beware of state highway signs with the shape of Oklahoma on them. That's not a finger pointing left! |

It is also the home of the “Ku Ku,” whose neon sign was lit up for us!

From Miami we took “that ribbon of highway”: the only remaining 9-foot sections of original Route 66.

|

| "Sidewalk Highway" between Miami and Afton |

It was our longest day of the trip in terms of driving, and rained pretty much all day. Not every place we saw had been as well kept-up as in Miami. Passing yet another closed business, T. remarked, “There wasn’t much to it when it was open!” She also misheard “there isn’t any interstate on this part of the trip” as “there isn’t anything interesting,” which could possibly have been a point. Although Claremore did have Will Rogers Boulevard, followed by Patti Page Boulevard. There was even an “Americanized Irish Pub,” though we did not choose to go in.

Finally, we arrived in Catoosa. This is technically where the “Tulsa” Hard Rock Café (Casino) is located, and T. always has to stop and at least buy a souvenir pin from every Hard Rock. Catoosa is also the home of one of Route 66’s iconic roadside giants, the Blue Whale.

And this was where I was so pleasantly surprised by our approach to the city. From this eastern suburb, Route 66 is just a two-lane country road. Sunset was approaching and there seemed to be no sign of urban sprawl anywhere. Then, gradually, the road became 11th Street right into downtown Tulsa. I saw that the former “Rose Bowl” had since become a church. There were many neon and other signs of Route 66 vintage.

Because we’d traveled so far that day, we were staying in Tulsa for two nights. This would give us time to explore the city and also catch our breath (and do laundry). We really landed on our feet, as our Airbnb was in a restored Victorian family home in the Heights (formerly known as Brady Heights, after someone whose name was recently dropped due to his association with the Ku Klux Klan. You didn’t expect that from Oklahoma, did you?)

Tulsa became a boom town early in the twentieth century, when "black gold" was discovered. One good thing about the oil boom is that it happened at a time when Art Deco was the prevailing style in architecture, so Tulsa is studded with interesting buildings. There is much to see and admire downtown, as almost all these structures are intact.

|

| Philtower Building |

Tulsa is also scarred by the interstate highway system. Someone thought it would be a good idea to just slice Tulsa apart, so even though our beautiful street—once connected to downtown by a streetcar route—was only a ten-minute walk away, we had to walk through an ugly underpass to get there. Another neighborhood that was chopped in two by an interstate, another short walk from downtown, was the historic district of Greenwood.

Like many people, and probably most white Americans, I’d never heard of Greenwood before about a year ago. Then I started hearing about it because this year, 2021, marks the centennial of a terrible event of racial violence in Tulsa, when many people were killed and the homes and businesses of black Greenwood residents destroyed. What this event was and should be called—riot, massacre, other terms—is one of the provocative questions asked by the excellent, and brand new, Greenwood Rising museum, which for this inaugural year is free to all.

|

| Mount Zion Baptist Church. The original church on this site was burned in 1921. |

I highly recommend Greenwood Rising. The staff are excellent, and the exhibits are moving and thought-provoking. Instead of telling people what to think, like all too many sources do (well-intentioned or not), this museum tries to share personal reminiscences and experiences. Its suggestions for dialogue could be a useful primer for our interactions in general.

I learned a ton here, and not just about Tulsa. I knew that the aforementioned KKK was formed in my native state of Tennessee, but was not aware that it was also the home of the first “Jim Crow” laws, in 1881. (Jim Crow, the general term for laws that segregated black and white Americans after slavery was ended, was named for a character in a minstrel show. We learned that at Greenwood Rising too.) Nor did I know that Ida B. Wells, after whom Congress Parkway in Chicago was recently renamed, had begun her campaign against lynching in Memphis in 1892.

The events of 1921 started when a black teenage boy and a white teenage girl were in an elevator together. There is no one alive who can tell what really happened, although the girl later recanted her claim that Dick Roland’s touching her had been an assault. Long before then, a white mob had gathered at the courthouse, potentially to lynch Roland, while a group of black men armed themselves and went there with the goal of protecting him. Because these men were armed for defense, for many years black Tulsans were blamed for the violence, even though most of the victims were black themselves.

Where I learned most at Greenwood Rising, though, was in the lobby. I was wearing a Route 66 T-shirt (I only brought two T-shirts from England, knowing that I would buy more), and I heard a woman say, “Hey, she’s wearing Route 66!” She and her friends, all black ladies from Chicago, came up and started talking to me about our trip. Then T. joined us and, after she explained that she needs to see people’s lips to understand what they’re saying, the first woman, whom I shall call B., lowered her mask to speak.

It was T. who put into words what I had been thinking and feeling, particularly since traveling through Missouri. “I’m in two minds about Route 66,” she said, “because it reflects a simpler time, that was a good time for people like us.” She gestured to me. “But, I’m aware that it wasn’t the same for your families.”

One of the other women, who’d told me she had relatives in Tennessee, nodded. B. spoke up and said, “Yes, absolutely. But at the same time, there were good times. We had family, and the church. We sometimes lived in all-black neighborhoods, but then we didn’t have to deal with systemic racism. Until we went to a shop, or applied for something.”

“Uh-huh,” the third woman said.

“Well, I’m glad to hear you say that,” T. said. I was too.

“And indigenous people,” B. went on. “I mean, Oklahoma is the state with the second-biggest indigenous population, but it’s between 2% of the people in America. And you know, we’re 13% of the population, we have a voice. But they don’t have a voice.”

“This is what I’ve been finding,” I said. “There’s not just one story.”

“Exactly,” B. said.

I’d be surprised if B. were older than I am. She used language, and certainly spoke from experience, that was vastly different from that of Mrs. L. from Lebanon, Missouri. Yet I feel as certain as I can be that if these women ever met, they would not dislike each other. In fact, they’d have a lot of values in common. Greenwood Rising is right about dialogue; there is no substitute for actually talking to people, face to face as individuals, instead of labeling or just interacting through a computer.

B. and her friends hadn’t come to Tulsa for a convention or a meeting; they were there just to visit the city. As she’d alluded to, Tulsa began due to the Indian Removal Act (Trail of Tears). Choctaw, Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Chickasaw, Cheyenne, Comanche, Apache, Seminole, and other peoples were moved to this land because the U.S. government thought it wasn’t worth as much as their old lands, east of the Mississippi. Oil changed that, but as Greenwood Rising made clear, the history of Oklahoma is one of black, white, and Native Americans mixing cultures, sometimes more successfully than other times.

It was Booker T. Washington who described the Greenwood District as “Black Wall Street.” The black (segregated) high school in Tulsa was named after him, and the class of 1921, 100 years ago, had this motto: “Climb tho’ the rocks be rugged.”

From Greenwood, we crossed the “urban renewal” divide again to reach the original, pre-1932 alignment of Route 66. A 1925 gas station along this route is so distinctive it’s given its name to the entire district: Blue Dome.

Then we continued downtown to admire the many Art Deco buildings. T. was looking for a memory card and thought she’d found the address of a computer store. We couldn’t find it, but when we went into a beautiful old building to ask, the woman at reception couldn’t have been more helpful. She insisted on looking the supposed store’s number up and telephoning herself: “I’m curious now.”

“Oh, I’m so jealous!” he said, and asked all about where we’d been so far.

In my previous post, I mentioned Cyrus Avery, who though born in Pennsylvania came to call Oklahoma home. While a more direct route for 66 would have gone through the center of Kansas, Avery convinced his colleagues that it should instead follow the existing trade route between Chicago and Tulsa. The 11th Street Bridge was named for him, and although it’s long been considered unsafe for traffic, this Art Deco masterpiece still spans the Arkansas River.

The 1916 bridge at its eastern end, Centennial Plaza. Photo by Janette Boyd

I really enjoyed our time in Tulsa. It was beautiful and diverse. We had Japanese food one night and Caribbean (the restaurant was run by a family from Dominica) the night before, and we could walk to everything we wanted to see. Our Airbnb had a hot tub in the backyard and a lovely dog who greeted us every time we came “home.” I highly recommend it.

Just skip the interstate if you’re driving from the east. And watch out: T. saw what she thought (and by now, expected) was a statue of a chicken, but then it started to cross the road!

Thanks to Jessica Dunham’s Route 66 Road Trip for background on this post.

1 comment:

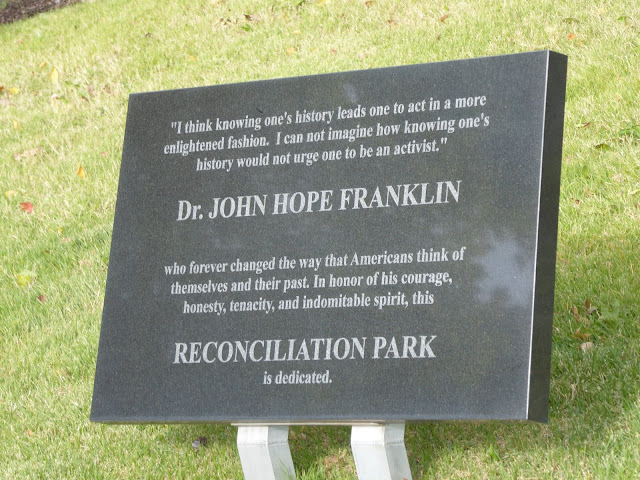

Another excellent demonstration of your dictum, "There is no substitute for actually talking to people, face to face...." And we love your concluding photo: I met Dr. John Hope Franklin when he spoke at a thee-week conference at the National Humanities Center in the Research Triangle, NC. He was a great historian and a very wise and gracious man whom I hold in the highest esteem! P & G

Post a Comment